Key Takeaways

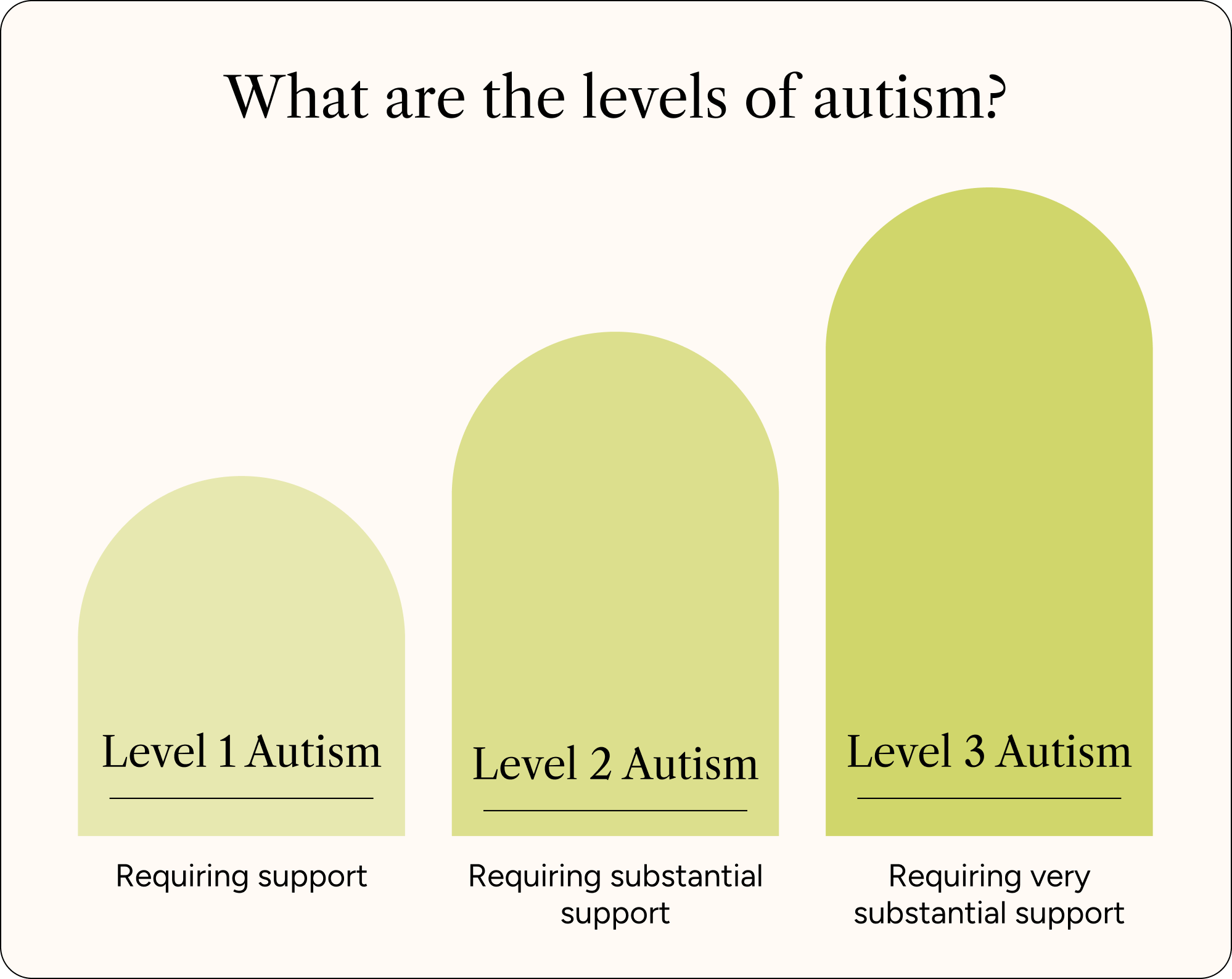

- Autism is not defined by ability but rather by support needs: Level 1 - requiring support, Level 2- requiring substantial support, and Level 3 - requiring very substantial support.

- Those diagnosed with autism will be assigned a level of support needs used in allocating services and accessibility resources properly.

- Experts agree that levels serve as a more inclusive system since support needs can change over time.

- Accommodations should be flexible and based on the individual's autistic experience.

As an adult diagnosed first with autism as a child and again as an adult, I have witnessed firsthand the change in the way the DSM, or The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, has changed to affirm autistic people. In 2013, the DSM updated its resources with an eye to supportive care.

Rather than labeling autistic people with misleading descriptors like high-functioning, low-functioning, or others, experts now categorize autistic individuals based on levels (one, two, or three). These levels indicate varying degrees of support needs, which are often fluid and can change over time.

Mental health professionals and patients can now navigate autism support without labels, a notable step forward in recognizing the individuality of care.

This DSM change also did away with the term pervasive developmental disorder, which encompassed disorders such as Aspergers and child disintegrative disorder. Instead, they were replaced by autism spectrum levels.

Kaila Hattis, MA, LMFT, founder and therapist of Pacific Coast Therapy, explains, “The change focuses less on what someone has to more on what someone needs, and changes the way families access services and disperse information on what their loved one needs."

While these three levels of autism don’t capture the full picture of autism spectrum disorder, they’re a move in the right direction to fuller, more nuanced autism treatment.

What are the levels of autism?

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that influences social interaction, communication, learning, and behavior. It’s not a disease, just a difference in how someone’s brain functions. However, these differences can pose challenges to thriving in a neurotypical world, which is why accommodations and support are vital.

Used in a medical setting, support levels help determine the standard of care autistic individuals can attain–though you probably won’t need these outside of a therapeutic setting, it’s helpful to know so you can advocate for yourself throughout your life. There are three levels of support:

- Level 1 Autism: Requiring Support

- Level 2 Autism: Requiring Substantial Support

- Level 3 Autism: Requiring Very Substantial Support

The levels of support are based on two core domains that make up diagnostic criteria for ASD: social and communication abilities (known as ‘social affect’) and restricted or repetitive patterns of behavior and interests (RBB), also known as self-soothing and self-regulatory behaviors or stimming.

And while intellectual or language impairment can factor into autism diagnosis, they are not integrated into the overall judgment of autism severity. Someone can be diagnosed with two levels, as well. For example, a person might be diagnosed as Level 1 for social affect, and Level 2 for RBB

Additionally, these autism support levels can be impacted by multiple factors like:

- Environmental changes

- Day-to-day demands placed on the individual

- Emotional states

Level 1 Autism: Requiring Support

Those with Level 1 autism require support in social communication and RRB. Like all ASD diagnoses, these must impact functioning on a daily basis. Oftentimes, they need support with:

- Understanding allistic (non-autistic) social functioning, cues, and norms

- Executive functioning such as switching or initiating tasks

- Managing heightened sensitivities to sensory input like loud noises, textures, strong smells, flavors, etc

- Moving through environments where the majority of people are allistic

- Managing restrictive and repetitive behavior present especially with functioning in social context

Those with Level 1 autism often struggle with initiating social interactions and may respond in surprising ways to their peers or colleagues, or may be uncertain what is expected of them. For example, those with Level 1 autism change topics or prefer to solely speak about one topic, like their special interest. Without therapies or interventions, those with Level 1 support needs might struggle socially or in unstructured environments.

Hattis says that this level of support is all about reminders and structure.

“These people can cope with work and personal relations but require reminders about social situations and have difficulty in managing the unexpected,” Hattis explains.

Support is needed even at the “lowest” level of autism support needs. That’s because autism isn’t simply a momentary difficulty with navigating the world, but rather a systemic and disabling challenge. Those in this category are most likely to hear the words ‘everyone’s a little autistic,’ which is both invalidating and untrue.

When it comes to support needs, Anat Joseph, LCSW and psychoanalyst, says consistency is key.

“Be patient with social differences and encourage independence while offering backup. Small accommodations—like extra time or helping to navigate social events—go a long way,” she encourages.

Here are some different ways to help with Level 1 support needs from mental health experts:

- Provide clear, written communication

- Quiet, sensory friendly areas manage overwhelm

- Provide flexible scheduling, or clearly communicate schedules whenever possible

- Give those with autism tools to advocate for themselves in social and work settings

Level 2 Autism: Requiring Substantial Support

Those diagnosed with Level 2 support needs benefit from more structure and communication support in allistic environments. The challenges in Level 2 autism are more significant, despite the presence of support. Folks often need:

- Extra support in school environments

- Supported employment settings

- Daily structures with managed predictability

Joseph says that building structure into the day of someone with level 2 autism can be integral to managing care. Repetitive behaviors can impede executive function or focus.

“Structure and routine are key. Help them build coping skills and social understanding gradually. Emotional validation is just as important as practical help,” she explains.

Some ways to help with Level 2 support needs are as follows:

- Ongoing neurodiversity coaching

- Visual or kinesthetic communication aids

- Clear scheduling

- Social worker support for autonomy

- Sensory-friendly community spaces and housing

Level 3 Autism: Requiring Very Substantial Support

Those diagnosed with Level 3 support needs face significant daily functioning challenges. Individuals may be non-speaking and use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) to express themselves properly, such as a tablet with marked words and visuals. Many times, those with Level 3 autism need:

- One-on-one support from an aide or other therapist

- Special education programs

- Assistance with daily living skills like cooking or dressing themselves

- Consistent and predictable routines

- Space to stim/use repetitive behaviors to self-soothe

- A range of mental health and holistic care professionals

- Community inclusion

- Help with restrictive, repetitive behaviors that can interfere with functioning in all spheres

While those with Level 3 autism are significantly disabled, they are no less worthy of support and care. Indeed, the best support is an inclusive community. Remember, the levels of autism are not a hierarchical system.

“Support often involves full-time care, but always prioritize dignity and autonomy where possible,” Joseph states.

Hattis agrees. “The level of autism support indicates the degree to which a person needs daily assistance to succeed in the world and not the level of their intelligence or potential,” she explains.

Whether a person is diagnosed with Level 1 or Level 3 autism is immaterial to their worth as human beings.

Limitations of autism levels

Even though the new DSM-5 levels of autism are more holistic and nuanced than previous editions, there are still limitations to this approach.

Levels can change over time

Maria Knobel, MD, Board Certified General Practitioner and founder of Medical Cert UK, says that "care might change over time, especially if an autistic person is in the care of a medical professional or therapist." In other words, these autism levels are considered flexible, as a person’s needs might change over time, and they’re in no way related to intelligence.

She continues, “Different types of support are dynamic, and can be scaled up or down depending on context, asset availability, and efficacy (health)."

Since support needs can vary over time, it’s important to think about environmental modifications that make daily functioning easier. Qualified mental health professionals are able to make suggestions to those ends.

For example, if grappling with self-care presents a challenge, pre-sorting medications can reduce the barrier to executive functioning. In children, transition periods in school can be difficult, so multiple reminders by teachers or aides can ease the process. In my personal experience, a quiet room is necessary to do my work, so my partner and I have come up with a plan to reduce any intrusions that can derail my functioning.

Dr. Knobel says that support levels can change significantly with children especially when proper interventions are introduced. Whereas a child might be marginally delayed at Level 2 at 6 years old, they may progress to Level 1 in adolescence. Conversely, adults who are diagnosed at Level 1 could, under stress, need more support indicated under Level 2.

Intensity of autistic traits can cut across levels

Levels are more affirming overall than labels of “high” or “low” functioning, but they have their limitations. An NIH report explains that both social communication and restricted and repetitive behaviors are two such areas that cut across the levels proposed in the DSM-5, and therefore must be considered for a more holistic view.

For example, some autistic people have ‘spiky profiles’—that is, their abilities vary widely across various domains. While they might have excellent functioning verbally, they might struggle, say, with sensory processing.

Joseph says that spiky profiles can often be a challenge in a clinical setting.

“This can be confusing to others because the person may appear highly capable in one setting and deeply challenged in another. Recognizing this helps us avoid assumptions and offer the right type of support where needed,” she explains.

As the proud owner of a spiky profile, I can function well socially for a time, but find auditory and kinesthetic sensory input often overwhelming. After hours in public, I might experience something called verbal shutdown, where my ability to speak and be spoken to degrades rapidly.

My personal support plan relies on noticing when my shutdown begins so I can take a step away from, especially auditory input. But in a clinical setting, I might appear functional—because I’m not underneath a constant barrage of input. In this way, I might appear to be at a Level 1, but occasionally I might be better suited for Level 2.

Other Considerations

While autism support levels have their limitations, they can still be used at home and in therapeutic settings to determine the kind and amount of support an autistic individual might need in the day-to-day.

“It’s important to remember that support levels are not a hierarchy of worth or intelligence. They’re tools to help us respond to real-world needs. Every autistic person deserves respect, inclusion, and individualized care—no matter their level of support,” Joseph adds.

Masking can also complicate matters. Masking refers to how autistic individuals might act more allistic to successfully navigate social settings. Masking can be taxing, however, and can lead to stressors that may change support levels over time. In fact, masking can lead to autistic burnout, a condition where those with autism, no matter their support level, require a period of rest to recover.

It’s therefore important to consider that needs change over the course of lives. Recognizing this allows clinicians and patients to be flexible with care plans.

Beyond the labels: Understanding Individual Needs

One thing becomes clear when developing a support plan for autistic individuals: because support needs can vary so widely and change, an individual needs-based approach is necessary.

Multiple prongs are vital when assessing those with autism, and support plans based on autism levels should focus on strengths first. Rather than conceptualizing autism as a “high functioning”/low support needs or “low functioning”/high support needs spectrum, a person’s unique profile should be considered in full.

“Talking about “abilities” or “functioning” (like “high-functioning” autism) can be misleading and overly simplistic. A person may have high cognitive skills but still require support navigating daily routines or managing sensory sensitivities. Support needs give us a fuller picture—it’s not about intelligence, it’s about the practical realities of someone’s life,” says Joseph.

Old paradigms of understanding autism were misleading because they assumed autism operated as an intelligence-based disability. Nor does having low support needs suggest someone with autism has a high IQ. Both concepts are out of date.

Related Conditions and Historical Diagnoses

The DSM-5’s major update both did away with historical diagnoses that harmed the autistic community and absorbed others that best exist on a support needs spectrum rather than as discrete disabilities.

Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD) was a term used in earlier diagnostic manuals to describe a group of developmental conditions, including autism, Asperger’s, Rett syndrome, and PDD-NOS (not otherwise specified),” explains Joseph.

PDD included a diagnosis called child disintegrative disorder (CDD), a rare condition characterized by children who lost their learned language and social skills at around age three, was also absorbed into the DSM-5’s new autism spectrum disorder criteria.

- Asperger’s Syndrome, named for the infamous Nazi Austrian physician Hans Asperger, was considered a subset of PDD, with the diagnostic criteria of disabled social functioning with high intelligence. An ableist conception linking social worth to intellectual ability and so-called ‘high functioning,’ it should never be used to describe autism spectrum disorder.

- Rett Syndrome is a rare neurological disorder, predominantly seen in girls, that disrupts brain development. It is no longer considered part of the ASD umbrella, and has instead been given its own categorization.

The DSM-5 attempted to consolidate all disorders that seemed to fit under the umbrella of ASD so instead it could focus on care support levels in a more efficient manner, while doing away with historically loaded terminology and syndromes that have their own unique categorization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How do you know if you have level 1 or 2 autism?

Support needs are used in therapeutic settings predominantly, and therefore are typically assigned during an autism diagnostics process. Those with Level 1 autism typically do not need as much support day-to-day as compared to those diagnosed with Level 2. Autism support levels can change over time, however, which should be kept in mind.

What is the difference between F84 0 and F84 5?

F84 0 is the current ICD-10 code that encompasses the DSM-5’s changes to autism spectrum disorder. It includes autism spectrum disorder, infantile autism, Kanner’s syndrome, and infantile psychosis. F84 5 was previously used for Asperger’s syndrome. While that code still exists, it is no longer used as that syndrome was absorbed in the DSM-5’s new definitions.

Does level 1 autism qualify for SSI?

While SSI offers financial support for those with autism, the criteria are quite limited. Child patients, for example, must have medical documentation of both qualitative deficits in verbal communication, nonverbal communication, and social interaction. They must also have significantly restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, and extreme limitation of one, or marked limitation of two areas of mental functioning. Adult restriction is much the same. Therefore, it is unlikely that level 1 autism meets that criteria.

How many levels of autism are there?

There are three levels of autism, broken down by support needs and impairment on a daily basis.

What are the levels of autism?

Autism has three levels as defined by the DSM-5: level 1 - requiring support, level 2 - requiring substantial support, and level 3 - requiring very substantial support.

Conclusion

When the DSM-5 changed their diagnostic criteria to reflect support care needs for those with autism, rather than continuing to use labels for autism, they began to lay the groundwork for evidence-based and nuanced care for those with the disability. While not perfect, autism support levels focus on care and quality of life rather than stressing intellectual ability, a net benefit for inclusivity and community.

If you’re an autistic person who wants to explore your support needs, Prosper Health can help in identifying your spiky profile, discerning whether or not you’re masking on a daily basis, and whether you’re in autistic burnout.

If you suspect you may be autistic but haven't been diagnosed yet, Prosper Health can help with that as well—offering accessible diagnostic assessments covered by most major insurance companies. Prosper also has exclusively neurodiversity-affirming clinicians who are ready to help—and 80% identify as neurodivergent themselves, or have a close connection with neurodivergence or autism, which means you’ll get empathetic care that prioritizes your unique mind.

Prosper Health can empower you wherever you are in your ASD journey.

Sources

American Psychiatric Association, D. S. M. T. F., & American Psychiatric Association, D. S. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Vol. 5, No. 5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Autism severity and its relationship to disability. International Society of Autism Research. 2023.

Restricted and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders: The relationship of attention and motor deficits. Developmental Psychology. 2017.

Brief Report: DSM-5 “Levels of Support.” Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2014.

A Systematic Review of the Assessment of Support Needs in People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020.

Cognitive Profile in Autism and ADHD: A Meta-Analysis of Performance on the WAIS-IV and WISC-V. Archetypes of clinical neuropsychology: the official journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists. 2023.

A Conceptual Analysis of Autistic Masking: Understanding the Narrative of Stigma and the Illusion of Choice. Autism in Adulthood: challenges and management. 2021.

Asperger syndrome. National Autistic Society. 2023.

Just the Facts: The DSM-5 and Autism Spectrum Disorder. VCU Autism Center for Excellence. 2015.

Disability Evaluation Under Social Security: 112. Mental Disorders - Childhood. Social Security Administration.

Disability Evaluation Under Social Security: 12.00 Mental Disorders - Adult. Social Security Administration.

Related Posts

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding Autism

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder. This means it’s a developmental disability involving an individual's neurological system. It is not a mental disorder or mental illness. ASD affects how people communicate, behave and process sensory information.

Some people believe that the term "spectrum" means everyone falls somewhere on the spectrum of autism. This is because autistic traits are human traits. Many people do have some features of autism, but this does not mean they have enough features of autism, at a high enough level, to be clinically diagnosed as autistic. In actuality, the term “spectrum” helps to highlight that there are many ways that autism can affect people differently. There’s a wide range of how autism presents in someone’s life. For example, there are some autistic people who need significant support, while others can live more independently. This is why clinicians now categorize autistic individuals based on levels (one, two, or three). These levels indicate varying degrees of support needs, which are often fluid and can change over time.

The diagnosis “autistic disorder” was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R)––a reference manual for mental health providers—in the late 1980s.

However, the DSM-5, released in 2013, resulted in a major change in language surrounding autism. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is now an overarching diagnosis, encompassing the older diagnoses of Asperger’s syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and autistic disorder.

Increasing awareness and understanding autism

People used to think autism spectrum disorder was rare, but many people are realizing it’s more common than they thought.

The Cleveland Clinic estimates that 1 in 36 children in the U.S. is autistic, and the CDC estimates that 2.21% of U.S. adults are autistic.

However, these percentages may actually be higher due to factors like misdiagnosis, underdiagnosis or late diagnoses. These occurrences are particularly common among certain groups, such as girls and women, people of color and those from marginalized communities.

This doesn’t mean autism is more common now than it used to be. Rather, autism awareness among healthcare providers is higher, especially now that there’s better access to tools and resources for continued learning. The general public knows more about autism, too. These advances help foster better understanding for autistic people as well as their families, friends and communities.

What is Identity-First Language, and Why Use It?

Most of us were taught that it is best to use “person-first language” when referring to disabilities. Person-first language intentionally separates a person from the disability, as in saying “person with diabetes” rather than “diabetic person.” This intends to emphasize the individual over their disability, showing that the disability does not define the person. However, not everyone views their disability as something that can, or should, be separated from them.

This is why identity-first language—as in saying “autistic person” rather than “person with autism”—is important to the autistic community. Many autistic people prefer identity-first language because it acknowledges that being autistic is a core part of who they are.

Understanding Neurodiversity Affirming Therapy: A Guide

Neurodiversity is a growing movement that celebrates neurodivergent perspectives and the many different ways people think and engage with the world. As the cultural conversation around neurodiversity has expanded, some institutions have begun evaluating ways to better include and uplift neurodivergent people. These changes are desperately needed, especially in mental health services. Neurodiversity-affirming therapy offers neurodivergent people mental health support that recognizes our value and embraces our inherent strengths.

.webp)