Key Takeaways

- Self-stimulatory behavior, or stimming, is a way autistic folks regulate sensory and emotional distress, seek sensory input, and express emotions.

- Stimming includes a diverse range of behaviors, not limited to hand-flapping, rocking, or picking at skin.

- While in the past, doctors viewed stimming as something that should be mitigated or reduced, stimming can be a meaningful tool for autistic folks to self-regulate.

- Stimming should only be treated if it’s causing an autistic individual bodily harm or distress.

Self-stimulatory behavior, or "stimming", is a physical behavior used by autistic and other individuals (including those who are allistic) to regulate emotional or sensory stress, sensory seek, and/or express their emotions. In autistic people, stimming is often repetitive and is a way to calm their minds and bodies.

Personally, I have stimmed my entire life in many ways. Notably, I am always carrying a rolling stim toy with me. It helps to ground me when I get anxious, or when the noises in a room are too loud or overwhelming.

Everyone stims, whether they realize it or not. If you’ve ever bounced your knee while bored, or clicked a pen open and closed, you’ve stimmed. But for autistic folks, stimming serves a key role in sensory and emotional management. It’s not something to fix, but rather something to understand.

In this article, we’ll explain what stimming is, why it happens, and how to support yourself or someone around you who stims.

What is Stimming?

Stimming, short for “self stimulatory behavior” refers to repetitive movements, sounds, or sensory experiences. Many non-autistic people stim. It’s a common way humans self-regulate. Autistic people may stim more frequently, intensely, or find it harder to suppress, but stimming alone isn’t diagnostic of autism. Many autistic folks, as well as anxious individuals, those with other mental health conditions, and allistic individuals, may rely on stimming in stressful environments, as well as to preempt stress.

Sanam Hafeez, PsyD, Director of Comprehend the Mind, says that stimming is a way to feel calmer during stress or overwhelm.

“Stimming can also help them focus or process information. It is a way to regulate their body and mind. Everyone’s stimming is unique, and it is a normal part of how autistic people cope,” she adds.

While many adults stim, stimming is reported more often among autistic individuals. Stimming is not part of the DSM-5’s diagnostic criteria on its own, but occurs more frequently in response to diagnostic criteri like sensory overwhelm, or other instances where autistic individuals need to calm or soothe themselves. The behavior is not limited to those with autism. Tapping your foot, listening to loud music, and bouncing your knee may be self-stimulatory behaviors; they’re simply more present in autistic folks and are part of our identity.

While stimming may reduce with age, autistic adults with autism still report stimming as a useful coping mechanism. Children typically have more obvious stimming because with age, adults learn to mask stimming due to social pressures.

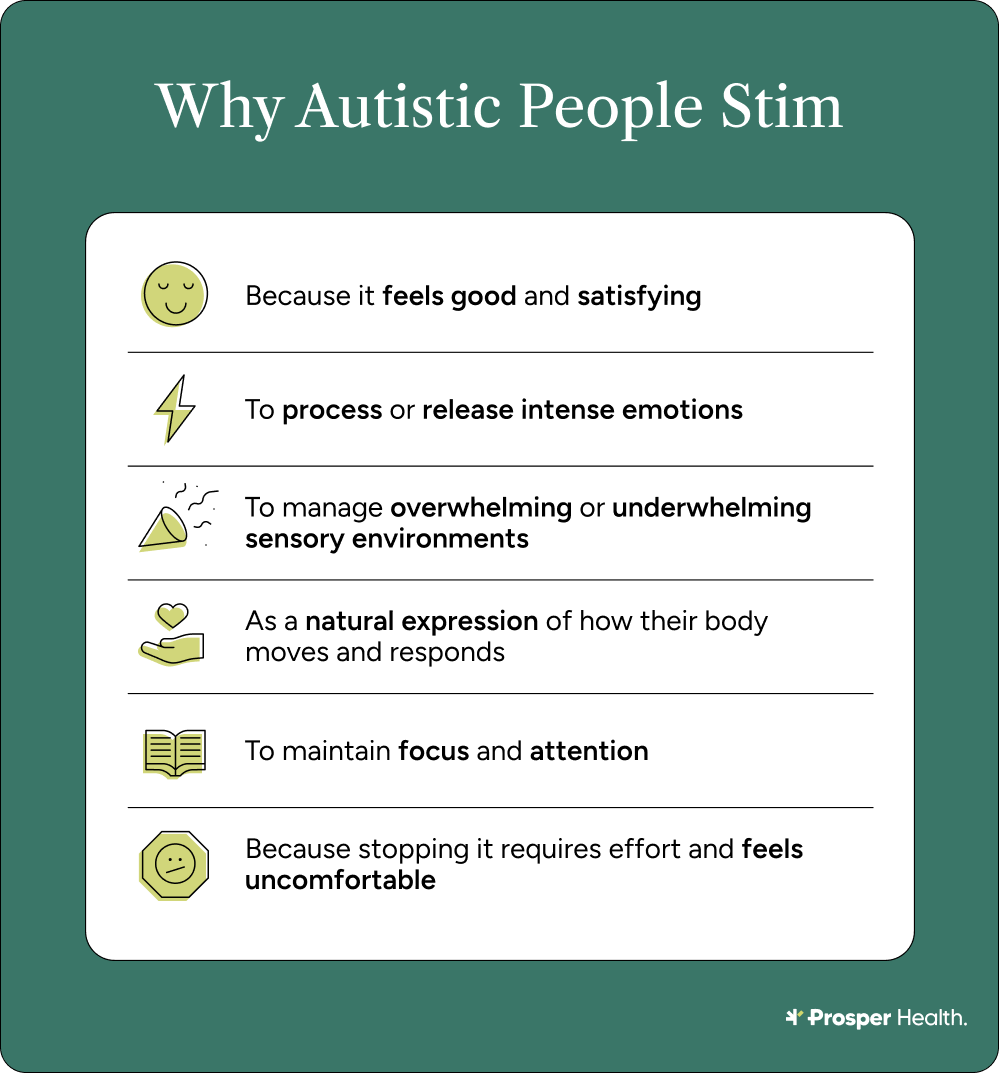

Why do autistic people stim?

There are many reasons autistic adults may stim. Jacqueline Shinall, PsyD, Prosper Health psychologist, explains.

“Autistic individuals stim for many reasons. One major contributor is regulation related to sensory input. People with autism can be more sensitive to sensory input, such as sounds, lights, textures, etc. or they can be much less sensitive to sensory input. People with autism may stim for other reasons as well, such as to help them focus or concentrate or to regulate emotions.”

There are a few major categories that stimming falls into: sensory regulation, emotional regulation, and self-expression.

Sensory Regulation

Sensory regulation is a major part of why autistic people may stim. Autistic people may experience differences in how they process sensory stimuli in their environments. So, when a room is too loud, or a task too overwhelming, autistic people may stim. In fact, stimming may be used to “narrow” the field of sensory input for autistic adults; they can make sense of an overwhelming environment by limiting their focus to a repetitive task, rendering it as familiar and predictable as possible.

Some sensory overwhelm can be caused by:

- Loud restaurants

- Brightly-colored spaces

- Harsh or overwhelming smells

It’s worth noting that this is a limited list; many things can cause sensory overwhelm—not only the physical.

Stimming offers a predictable physical response that can help self-soothe and prevent a meltdown.

Emotional Regulation

Autistic folks may also attempt to regulate their emotions by stimming. Autistic individuals experiencing joy might flap their arms or skip. Or, an autistic person struggling with an emotional response due to sensory processing and social differences may lean on stimming behaviors to help down- or up-regulate their control on their emotions.

Autistic people often use stimming to regulate emotions. When emotions feel overwhelming or unclear (whether from sensory overload, social uncertainty, emotionally charged situations, or excitement) stimming provides grounding and release.

Situations that may elicit stimming include:

- conversations

- Social interactions that went unexpectedly

- Emotionally intense events, such as funerals

- Moments of joy or excitement

Stimming offers a physical outlet for big feelings, helping autistic people process emotions and regain executive functioning.

Communication

Stimming may also allow autistic people to communicate their needs and connect to their communities. In a world that often misunderstands autistic individuals’ intentions and behaviors, stimming offers a mode of communication, especially for those with higher needs. Social acceptance of stimming allows allistic individuals to view stimming as a positive way for autistic folks to communicate their needs, their excitement, and their emotional state. Stimming can be a nonverbal way for autistic folks to relate their emotions, opening the door to a more inclusive understanding of how we communicate.

Self-Expression

Stimming has also been reported in studies as a part of authentic autistic self-discovery and expression. In a 2024 review, researchers Petty and Ellis investigated their own relationships with movement, including stimming, dance, and exercise. They discovered that movement can be an essential part of an autistic toolkit for not just authenticity but also well-being. Some of the ways they reported stimming can help are:

- Enhanced focus

- Routine creation

- Sensory regulation

- Increased interoception

Not only can stimming be a way for autistic folks to manage their own sensory input, but it can be a useful way to reconnect to our bodies and minds, preempting autistic shutdown or burnout.

“The same person might use different types of stimming depending on their needs in the moment, the environment they're in, and what sensory input they're seeking or avoiding. Many autistic people develop a repertoire of stims that serve different purposes throughout their day,” Dr. Shinall explains.

In my own life, I play cello as part of a constellation of stimming, and it preemptively helps me to avoid dysregulation. When I don’t include cello or other forms of movement as part of my autistic toolkit, I find I am more often overwhelmed in my daily life.

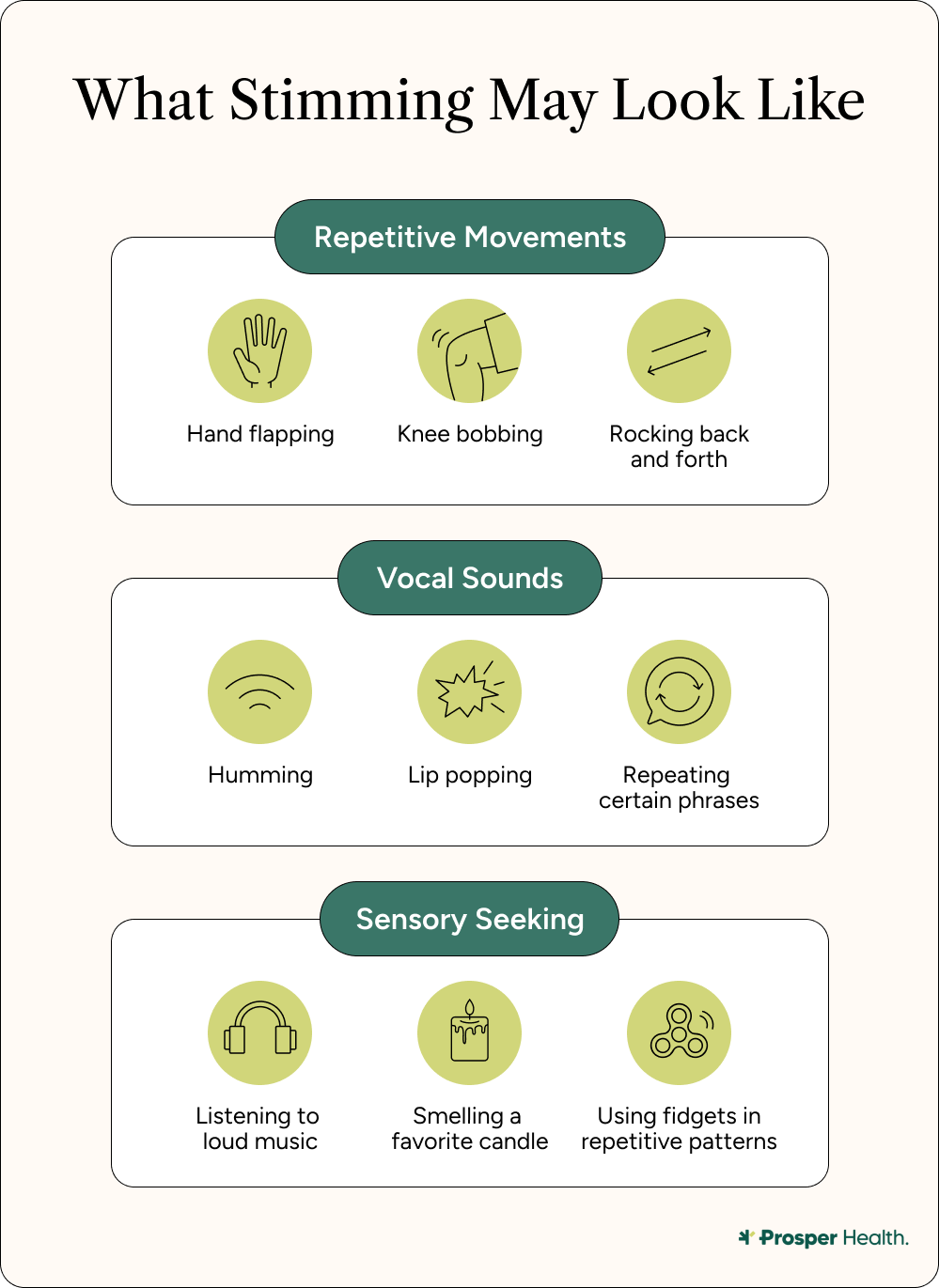

What are different types of stimming and what do they look like?

There are many types of stimming; no two people stim the same way. With that said, there are overarching sensory categories of stimming to be aware of.

Movement Stims

Movement stims are repetitive body movements. The vestibular system, which is linked to the inner ear, controls balance, and is employed. Some examples of movement stims are:

- Hand flapping

- Body rocking

- Head tossing

- Fidget toy use

Tactile Stims

Tactile stimming involves feeling different textures and surfaces. Some common examples are:

- Running hands over fabric

- Rolling textured objects in hands

- Chewing objects

- Repetitively touching objects

Visual Stims

Visual stims focus on visual input. Some examples of visual stims are:

- Focusing on lights

- Staring at patterns

- Changing the light in a room rhythmically

- Focusing on movements of objects, such as a rolling ball or a familiar TV show

Auditory Stims

These stims rely on different levels and kinds of sounds. Some examples include:

- Listening to certain sounds repetitively

- Playing a song over and over again

- Tapping to hear a sound

- Covering and uncovering the ears

Vocal Stims

Vocal stims involve the individual producing sounds for sensory seeking. Some include:

- Echolalia (making repeated sounds and phrases)

- Humming

- Singing a song over and over

- Lip popping

Taste and Olfactory Stims

Taste and olfactory stims focus on sensory seeking. Some examples are:

- Eating foods with certain textures

- Smelling items with certain scents

- Licking or tasting objects

What are some misconceptions about stimming?

Stimming is often the target of psychological interventions, especially when it first appears when we’re children. For so long, it was deeply stigmatized and doubted as useful. But autistic adults shouldn’t have to hide their stimming; it’s part of what makes us unique—and helps us to regulate our bodies and minds.

“Many people assume stimming is “weird” or “wrong” because it looks different from what they consider normal behavior. Some think autistic individuals are misbehaving or seeking attention when they stim,” Dr. Hafeez says. “People often fail to understand that stimming is a natural way to manage emotions. Stimming is a normal and important way for autistic people to cope with their feelings and environment.”

The truth is, stimming is a normal part of life for an autistic person. Myths about stims abound. Here are a few of them, debunked.

Stimming is always bad and/or disruptive

The short answer to this is: stimming is often helpful and the least disruptive option for autistic people to regulate their emotions in the short term.

Dr. Shinall adds, “Stimming is actually very important for many people, which helps to regulate emotions or sensory overwhelm, focus, decrease anxiety, among other benefits. Attempting to stop or suppress stimming behaviors typically leads to an increase in emotion dysregulation and may impact things like focus and communication.”

Non-injurious forms of stimming are adaptive and may help to reduce anxiety overall.

Stimming is always a response to distress

For me, stimming is not always a response to distress. Sometimes, I use stimming to wake my brain up. For example, if I eat something delicious I’ll often rock back and forth, or I’ll play cello to begin to focus before my workday begins. Others might find solace through dancing or other forms of movement.

“While stimming is often used to help someone feel calmer or more regulated, many people stim when they are feeling a wide range of emotions. For example, some autistic individuals will engage in hand-flapping when they are feeling very happy,” Dr. Shinall elaborates.

The act of stimming is pleasurable, helpful, and regulatory.

Stimming is always obvious and socially unacceptable

The social acceptability of stimming has its roots in trying to “train out” certain undesirable behaviors. However, because of masking, stims can be hidden or reduced so that they are less noticeable. Pen clicking, leg bouncing, nail biting and finger strumming are all examples of socially acceptable stims that even allistic folks do.

Stimming is always a sign of autism

Everyone stims, not just autistic folks. In fact, there is significant overlap in stimming behaviors in ADHD individuals and autistic individuals. And, since everyone stims, neurotypical folks, not just neurodiverse, do as well. Some common neurotypical stims are:

- Nail biting

- Pen clicking

- Leg bouncing

- Foot tapping

- Listening to loud music

Stimming is a form of tic

Tics, which are a neurological response to premonitory urges (like uncomfortable sensory input), are markedly different from stims. While they may coexist in the same person, tics are involuntary actions, whereas stims are voluntary. Also, tics, which are generally indicated in childhood and may be part of a neurological disorder like Tourrette’s Syndrome, tend to decrease over time. Stims, on the other hand, are a lifelong sensory response to manage external stimuli.

Stimming is one of the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism

It’s also important to know that stimming actually isn’t a part of autism diagnostic criteria, Dr. Shinall explains.

“Actually, stimming is not even mentioned in the autism diagnostic criteria. People often confuse repetitive behaviors that are consistent with autism with stimming behaviors. Some stims could be repetitive behaviors, such as hand-flapping or repeatedly jumping, but other stims are not consistent and can be seen in the general population (e.g., leg shaking),” she adds.

Stimming is not considered a “repetitive behavior” under these criteria, and therefore are not necessary for or indicative of autism, since people without autism also stim.

Should stimming be treated?

Stimming is not harmful in most cases and does not require clinical intervention, says Dr. Hafeez.

“These behaviors have a job. They help people settle their nerves, feel more grounded, or manage moments of stress and sensory overload.”

Dr. Shinall is emphatic: stimming should not be treated with a goal of eliminating the behavior.

“Rather, treatment around stimming should focus on ensuring the person is using a safe and effective stimming technique to regulate,” she says. “Treatment can help a client understand when and how to use stimming behaviors that may help with regulation or other challenges. Also helping clients advocate their needs and ensure others are accepting of their stims.”

If I didn’t have my stims, I don’t think I would be as functional as I am today. Stims help me to manage my emotions when they feel too unruly for my body, and they help me manage my stress when I get overwhelmed. Unfortunately, many autistic adults were exposed to psychiatric practices that tried to “train” stims out of them. Unless stimming is causing distress or harm, the focus should be on making the autistic person more comfortable, confirms Dr. Hafeez.

If an autistic person wants help regulating their emotions, clinicians can offer interventions, like discussing emotional regulation skills, using sensory tools, or making adjustments to their environment to feel more comfortable. Some autistic people might want to mask their stims for social acceptability purposes, while others choose to stim authentically as a part of unmasking. It’s up to the individual to decide—not society.

What about distress-driven or self-injurious stimming?

While most stims are not destructive or harmful, sometimes autistic people may have self-destructive stimming like hitting, scratching, or biting. These responses are most often linked to distress, rather than an intent to self harm.

Dr. Hafeez confirms that when stims begin to harm the individual, the focus should be on determining the root cause of distress, rather than blaming them for self-harming.

“It only becomes something to work on when the behavior is hurting the person, disrupting daily routines, or creating problems they’re worried about. When that’s the case, the focus is not on “stopping” the behavior. A clinician would want to understand what the person is getting from it and then offer other ways to get that same calming or organizing effect,” she says.

When I was younger and had uncontrollable trichotillomania, I pulled out nearly all of my eyelashes. I didn’t want to harm myself—but pulling out my eyelashes was a stress response because of bullying and anxiety. Once my caregivers noticed the root cause of my anxiety and I was able to change schools, my trichotillomania decreased drastically. Similarly, as an adult, I will return to trichotillomania in times of intense stress; it’s often the only warning I get that my body feels wrong and should make an effort to change something in my environment.

In-the-moment interventions are therefore always preferable. Redirecting harmful stimming behavior in a way that isn’t punitive allows autistic people their autonomy and protects their mental health. If self-destructive stimming happens relatively often, it’s best to get a clinician’s assessment in ways to find better support to reduce stressors. Remember: stimming isn’t a problem but rather a coping mechanism.

How to embrace and support stimming

Stimming is a valuable tool in an autistic person’s toolkit to help regulate their emotions, mind, and body. It should be embraced rather than devalued.

Stim toys, for example, are a great way for autistic adults to stim in a tactile manner. My own favorite features a ridged body with a spinning top. It helps me stay grounded in the moment when I can’t indulge in any movement stims like rocking or tapping, and also appears more “socially acceptable” since many allistic folks use stim toys, too.

Since stim toys and stimming overall has become more socially understood, autistic folks can feel safer unmasking the stims that they were either trained out of or masked.

Dr. Hafeez says that learning which stims feel comforting can help an individual accept yet another facet of their autism.

“When the individual chooses stims that help them stay calm and focused, it can support daily functioning rather than interrupt it,” she adds.

Here are some ways autistic folks can embrace their stimming:

- Practice stimming in front of trusted friends

- Buying stim toys

- Identifying personal stims, and experimenting with new ones

- Have discussions on community boards about ways to stim

- Speak to a therapist about ways to unmask, if desired

Stimming is a beautiful part of autism that truly helps to ground the individual. To that end, protecting and supporting stimming should be top of mind for anyone who cares for an autistic person.

“It makes a real difference when the people around an autistic individual understand what stimming actually is. Families, teachers, and coworkers who see it as a coping tool instead of a problem remove a huge layer of pressure,” Dr. Hafeez says.

Here are a list of ways allistic friends and family can support stimming:

- Allow them to practice stimming in front of them

- Ask questions about how they can make stimming more comfortable

- Ask how they can make an environment more sensory friendly

- Set out fidget spinners and stim toys to be used

- Be open to understanding and nonjudgmental

- Learn patterns of behavior that might indicate when an autistic person is stimming out of overwhelm

- Provide accommodations at work

Remember: stimming should be supported and embraced, because it’s a natural extension of sensory regulation for autistic people.

The bottom line

Stimming is simply a part of life for autistic folks; it should never be stigmatized. It’s a way for autistic people to regulate sensory and emotional distress, seek sensory input, and express emotions. Allistic friends and family should support their stimming autistic friends—especially adults who are making the effort to unmask for the first time. Stimming is a valuable tool, no matter how obvious or masked.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are some examples of stimming?

Stimming can manifest in a number of ways, but some of the most common are leg bouncing, rocking, twirling hair, flapping hands, listening to loud songs over and over, or touching interesting textures. Some of these, such as twirling hair and leg bouncing, appear more neurotypical and can therefore serve as part of masking for an autistic person.

Can you stim and not be autistic?

Yes! Everyone stims, including allistic (neurotypical) folks. There is also a significant overlap in ADHD and autistic individuals when it comes to stimming.

Is stimming bad?

Stimming is typically a response to environmental stressors that allows an autistic person to find equilibrium, or a preemptive behavior to keep equilibrium. It is not bad, but rather a coping mechanism. However, distress-driven stims that cause harm to an autistic individual require gentle in-the-moment intervention and redirection. It’s worth noting that in that rare case where a stim harms the person, it’s not their fault and should not be punished.

Can eating be a stim?

Yes, eating certain foods can be a stim. It falls under the sensory modality of taste, and can be grounding and calming, especially when stressed. Chewing may also be a component, as it can be calming to some individuals.

Sources

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11461748/

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1362361318774559

https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/epub/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1362361319829628

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10803-021-05312-1

https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1309&context=ur_cscday

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1362361319829628

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10465631/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19460171003714989

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/integrative-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnint.2013.00027/full

https://iaap-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aphw.12554

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11860154/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1353802019300367

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3992090/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6728747/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1750946721001392?via%3Dihub

Related Posts

Masking Autism: What It Is and Why It’s Exhausting

Imagine you’re hanging out with a group of friends. On the outside, this scenario looks like a typical get-together: Everyone is laughing, making eye contact, and visibly comfortable with one another.

But for some people, there is a very good chance that much of their behavior is the result of masking, or a concealment of their autistic traits. Sure, these people may come off socially at ease, but a debilitating dance is taking place behind their eyes.

“After I've been hanging out with people, I need to take a nap for one to two hours…my brain literally needs to shut off. I feel like a computer that needs to reboot,” says Aura Marquez, an author living with autism.

Marquez says she’s been masking since she was in late elementary school: “It’s gotten to the point where I can’t turn it off.”

Masking autism is how many neurodivergent people navigate a neurotypical world, so it’s important to understand the reasons behind this practice in order to minimize stigma. While masking may provide some benefits, it’s important to also remember the toll this behavior takes on one’s mental health.

That why learning how to also unmask, under the right conditions, is essential to helping autistic people feel comfortable in their own skin. This article will explore options for those who wish to stop masking, as well as support for those who do mask.

Meltdowns in Autistic Adults: Why They Happen, What They’re Like, and How to Live with Them

When many people hear the word “meltdown,” they might envision a kicking-and-screaming child, lashing out because their parent or caregiver said “no.”

While that is an accurate description of a typical child meltdown, a meltdown in an autistic adult is entirely different, and not to be confused. In fact, in many cases, meltdowns in autistic adults can look like the antithesis of a childhood tantrum. Instead of engaging in "why won't you give me what I want!?" goal-oriented behaviors that are synonymous with tantrums, autistic adults usually need to get away from people and into a calm, dark, safe space during a meltdown.

The most important thing to remember about an autistic meltdown is that it’s not a choice, but an involuntary nervous-system response to intense overload or stress. If someone is experiencing a meltdown, they are not intentionally acting out: They are dealing with complex emotions just like the rest of us, and don’t deserve the ongoing stigma that is attached to autism—and by extension, meltdowns.

Victoria Mindiola (they/theirs/she) is an autistic person who works as an inclusion consultant and educator, focusing on advocacy for neurodivergent students. When Mindiola experiences an autistic meltdown, they say they frantically need “to find a place that is safe and dark and quiet and empty of people.”

Unfortunately, the stigma around autism and meltdowns remains because adult-focused research and resources are still lacking. While there’s plenty of research available on autistic meltdowns in children, there is limited data from the perspective of autistic adults.

In this article, we’ll provide a comprehensive breakdown of autistic meltdowns in adults: What they are, why they happen, how to identify early signs, and how to support yourself or someone else.

Sensory Overload in Autistic Adults: Why It Happens and How to Cope

For autistic and neurodivergent adults, sensory overload can feel like it hits all at once. Imagine you’re in a crowded restaurant. At first, the talking all around you becomes intrusive, and you can’t concentrate on the person across from you, no matter how hard you try. Then the sound of repeated clinking of glasses and forks on porcelain intensifies, grates at your nerves, and suddenly the smell of the woman’s perfume at the table next to you becomes overwhelmingly strong.

Suddenly, you’re in full-body panic mode because this combination of sensory experiences is simply too much. Allistic people are able to compartmentalize and block out these types of input, but autistic people often cannot.

Sensory processing differences—formerly referred to as a “sensory processing disorder”—are the variations in how the brain receives, interprets, and responds to information gained through your senses from the environment and the body. Autistic people’s sensitivity to stimuli will vary depending on the individual.

Sensory overload, on the other hand, can happen when a neurodivergent person’s brain becomes so overwhelmed by sensory information in an environment (think: sights, sounds, smells, textures) that their body goes into a state of panic and fight or flight mode.

“Sensory overload, or strong sensory input, can often be described as ‘physically painful’ or ‘making my skin crawl’ by autistic adults,” says Jackie Shinall, PsyD, head of reliability and quality assurance at Prosper Health. “For example, they don’t necessarily feel anxious or stressed by the input, but rather uncomfortable overall, especially physically.”

While anyone can experience sensory issues and sensory overload, they are especially common among autistic adults and neurodivergent people more broadly. In fact, a 2021 study published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders surveyed autistic adults and found that 93.9% reported being extra sensitive to sensory experiences. Autism and sensory overload often go hand-in-hand.

If you have questions about sensory overload in autistic adults, you’ve come to the right place. In this article, we'll cover what sensory overload is, why it happens, what it feels like, and how to prevent and recover from it.

.webp)

.png)